This map depicts the layout of the Cassino area as it appeared when the New Zealand Corps attacked the Italian town in February and March 1944. The New Zealand Corps arrived at the town from the east. Its objective was the Liri Valley, the entrance to which is at the lower left corner of the map.

The Benedictine monastery towering above the town on Monte Cassino was destroyed by aerial bombardment on 15 February because it was assumed that the Germans were using the site as a lookout. At midnight on 17 February members of the 28th (Māori) Battalion crossed the Rapido River from the east. They briefly captured the railway station but reinforcements were unable to cross the destroyed rail causeway and the Maori were forced to retreat back across the Rapido under heavy enemy fire.

After the aerial bombardment of the town and a delay caused by poor weather, the Corps launched a renewed attack on Cassino from the north on 15 March. The Indian and the New Zealand Divisions of the Corps attacked side by side: the Indians captured Castle Hill and the New Zealanders entered the northern part of the town. The attack was costly due to the determined German resistance, particularly around the Hotel Continental, and the difficulty of bringing armoured and artillery support through the ruined streets. With the New Zealand Division’s casualties nearing a thousand, the attack was called off on 23 March.

Cassino finally fell to the Allies in May 1944. Most of the German defenders withdrew after being outflanked, and the town and the ruins of the monastery were occupied by British and Polish troops.

Credit:

From McGibbon, Ian (ed) The Oxford Companion to New Zealand Military History (2000)

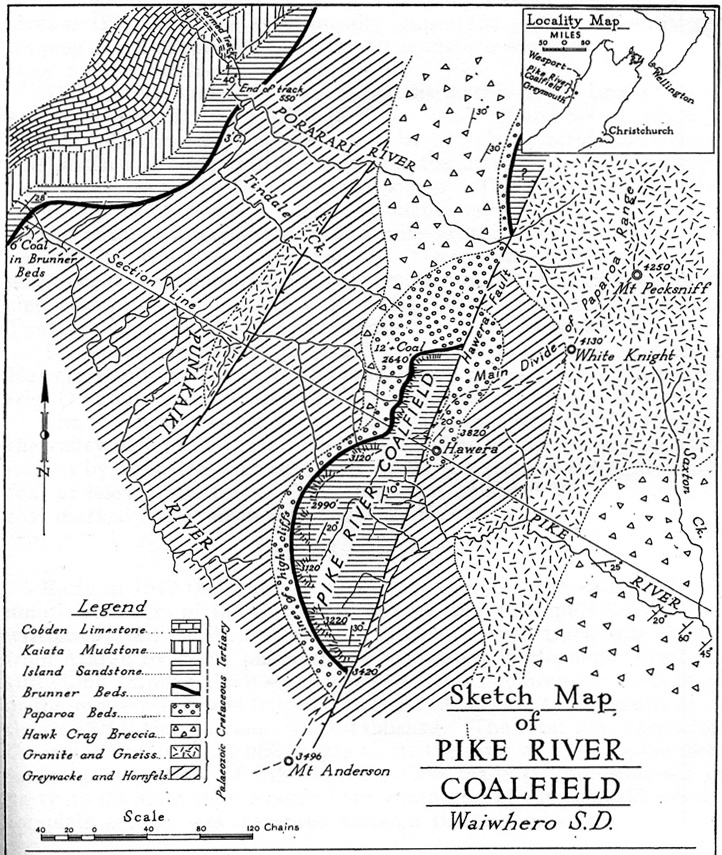

Map of the Cassino area, where New Zealand troops fought February-March 1944.

Reddit

Reddit Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook Google

Google StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon